Mentoring - The Benefits, Skills, and Pitfalls

May 25, 2022

Mentoring has a triple benefit. It benefits the mentor, the mentee, and the organization, so it is not surprising that people and culture, or human resource, departments are keen to set up mentoring programs. Why then do many mentoring programs fail, and what are the pitfalls?

The idea of mentoring can be traced back 3000-years to Homer's Odyssey. In this Ancient Greek epic poem, Odysseus entrusts his young son Telemachus to the care of a mentor, when he goes off to fight in the Trojan War. This history is likely the reason for the stereotype of the older, successful, man mentoring a young ambitious one. It also highlights the current need for those women, who have successfully navigated to the top, to mentor a new generation of women leaders.

Mentoring Definition

In a modern and business context, mentoring can be defined as a developmental partnership between a Mentor, a leader with expertise in one or more areas, and a Mentee, an individual seeking learning and growth in these areas.

Understanding this definition helps to avoid the first pitfall of providing mentoring where training, coaching, or even counseling would be a better prescription. There are clear overlaps in skills between all these activities but just as Panadol might help a headache, it’s not a substitute for an antibiotic.

To be clear, counseling is giving professional help and advice to resolve someone’s personal or psychological problems. Counseling in the workplace is often required when individuals are unaware of the impact of their behaviors and or are not taking responsibility for them.

The definition of coaching is much more fluid, and in the minds of many interchangeable with that of mentoring. For me, coaching is a series of confidential conversations to help the coachee move from point A, where they are to point B, their goal or objective. Since many of the obstacles in achieving a goal are mindset, an effective coach can both challenge and support an individual to break through limiting beliefs with listening and well-executed questions.

A coach, in the business context, may not need to possess the same skill sets as their coachee, as they are not teaching anything but instead revealing the resources the coachee already had.

Training, however, is the transfer of skills, usually in a one-to-many situation, however, in the case of a sports coach, this training could be one-to-one, hence the confusion.

Mentoring Pitfalls

During my career, I have been asked by clients to rescue a mentoring program for several reasons. Typically, the mentor and mentee are not meeting, or the mentor is becoming over-responsible for the mentee and feeling overwhelmed.

These issues can be avoided by:

- Setting an upfront contract

- Providing skills for mentors

- Effectively matching mentor and mentee

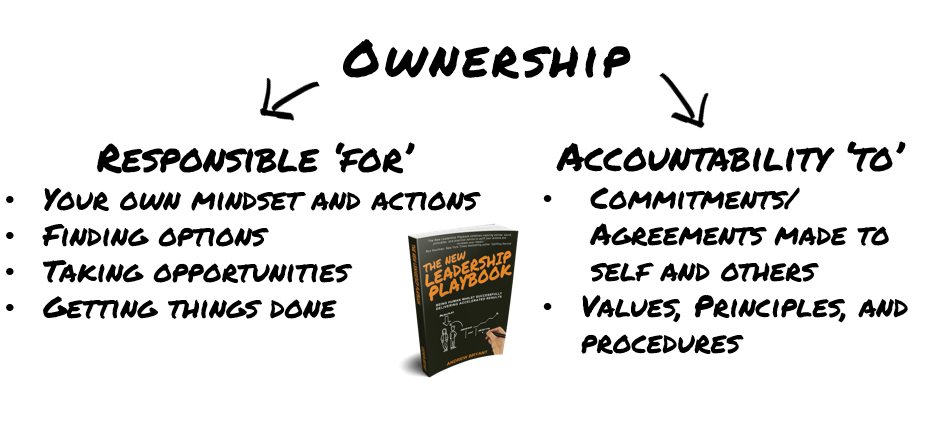

In ‘The New Leadership Playbook – Being Human Whilst Successfully Delivering Accelerated Results', I emphasize the importance of ownership and clarify the distinctions between responsibility and accountability.

For either mentoring or coaching to be successful, the coachee or mentee must take ownership of the process and be clear about what they are responsible for and accountable to.

The organization should set these expectations at the outset of a mentoring program, and the mentor should make these things explicit in an upfront verbal contract with their mentee/s. Doing this avoids the mentee expecting the mentor to do things for them, and the mentor burning out and leaving the program.

Skills for Mentors

A common error is that just because someone is senior and successful in an organization, they will make a great mentor. Mentoring, like anything, is a skill that must be developed.

Here is a list of six skills to consider providing support for mentors to develop.

- Supporting – Building rapport and unconditional positive regard

- Listening – Acknowledging what is said, and what is behind what is said

- Validating - Effective cheerleading of growth and development

- Questioning – How to ask both precision and meta-questions

- Feedback – How to deliver observations and challenge to exhibit new behaviors

- Guiding and offering perspective – When to tell and what to tell

Just acknowledging that these skills can be improved is of huge benefit to the mentor and the mentoring program.

Effectively Matching Mentor and Mentee

Telemachus was given a mentor by his father Odysseus, and I doubt he had much of a say in the matter. During my own life, I have sought out my own mentors when I wanted wisdom and guidance.

So, should the people department assign mentors, or expect employees to find their own?

Each approach has its downfalls and depends very much on the culture of the organization.

The first consideration is identifying who will benefit from mentoring, as distinct from coaching, or training. Then a pool of mentors needs to be identified, and if necessary, trained.

In my experience, a good mentor is:

- Someone who has experience in a specific field

- Someone interested in developing others

- Someone prepared to take another by the hand and guide them through the territory

- Someone who asks questions that the mentee doesn’t ask themselves but ought to

- Someone trustworthy who inspires confidence

- Someone who will be there in time of need

Mentoring Cultures

In learning cultures, mentors are elevated in status, so there is an incentive to be known as a mentor.

Information can then be shared with prospective mentees about how they can go about approaching a mentor. They can be supported to have clarity about what they want from the relationship, and their level of ownership of the process.

It has been deeply satisfying for me to see a failing mentoring program turned around, and to see the triple benefit to the mentee, mentor, and organization.

As a mentor myself, I consider the conversations, I have had with my mentees, as part of my legacy.

Get a FREE Chapter of The New Leadership Playbook

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.